The model’s calculations closely matched experimental study results for those species, which gave the authors confidence that their approach could reliably reconstruct dexterity in the fossilized hands.

The team first tested the accuracy of the models by using them on living humans and chimps with known muscle parameters.

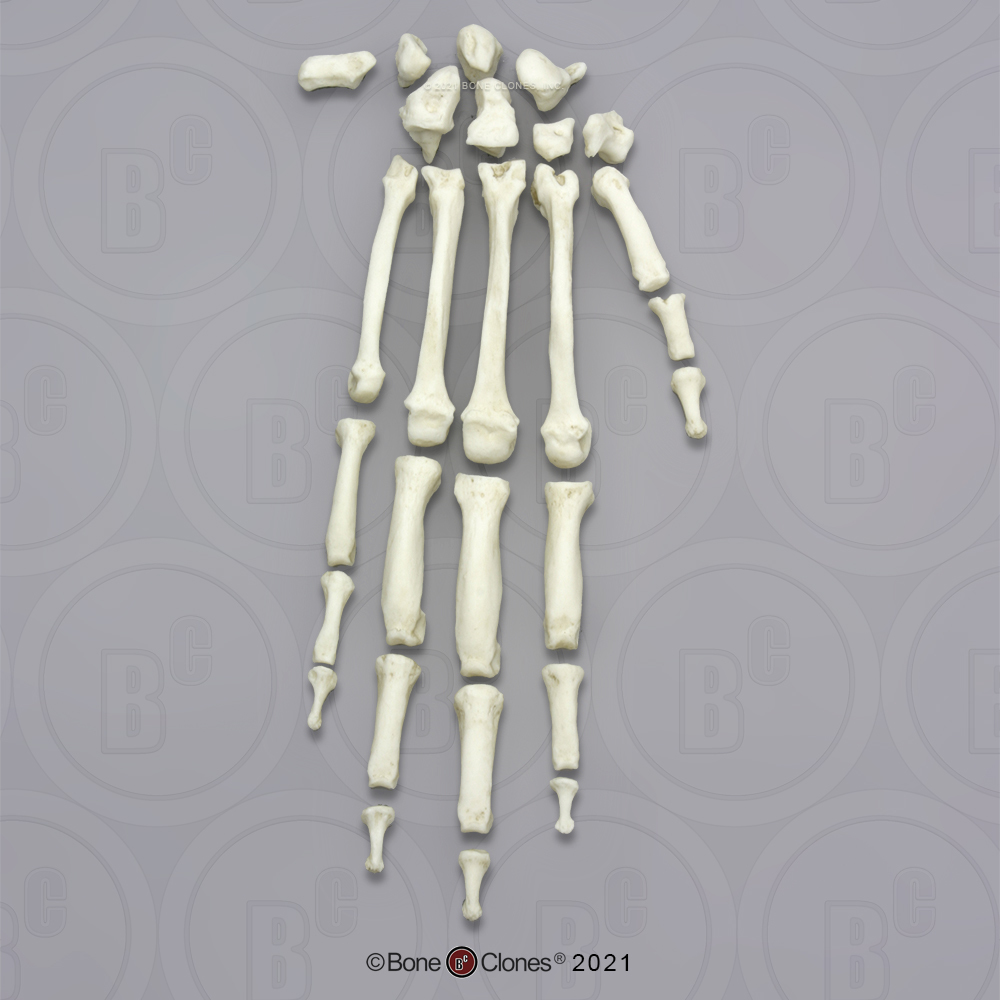

They then used a biomechanics model to recreate how muscles would have been able to manipulate those various thumbs, providing a look at how they once functioned. Among those specimens were some intriguing two-million-year-old hand bones from South Africa’s Swartkrans cave, that may be either early Homo or Australopithecus robustus. The team compared fossilized hands and thumbs of a suite of species ranging from Australopithecus afarensis, at nearly four million years old, to early Homo sapiens, to Homo naledi to modern chimpanzees and humans. So Harvati and colleagues put some digital flesh on varied bones. Such straightforward comparisons of thumb and finger shapes and their similarity to our own are useful but they don’t tell the whole story, because in nature, different shapes and forms sometimes perform in similar ways. “Experimental studies have shown that humans use forceful precision grips when they make and use stone tools, so it's often thought that this ability in humans evolved in response to tool use,” Kivell says.Īnthropologists have spent a lot to time comparing hand, finger and thumb fragments left behind by species across many branches of the human family tree over millions of years to see where and when this ability developed. But humans excel at precision grips that match the pad of the thumb to the pads of the fingers-and for those a powerful thumb is essential. Tracy Kivell, a paleoanthropologist not involved in the study who specializes in the morphology of primate hands at the University of Kent and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, notes that many primates with different hands are capable of precise and powerful grips. Over time natural selection could have refined these anatomical changes based on the many ways humans used their hands and which of those proved most rewarding, like smashing animal bones to collect their high energy marrow. But as our ancestors forsook life in the trees, and increasingly began to make and manipulate objects, shorter fingers and longer opposable thumbs would have produced a hand assembly that got better and better at grasping. Shorter thumbs and longer fingers are helpful for climbing.

“We believe that constituted a crucial evolutionary advantage which likely enabled the subsequent gradual development of complex culture in our lineage,” says Harvati, co-author of the new study published in Current Biology. That time period is a notable one as it came before major evolutionary events, including the rise of the large-brained Homo erectus 1.9 million years ago, that species’s dispersal outside Africa 1.8 million years ago and the replacement of primitive stone tools by sophisticated Acheulean handaxes about 1.76 million years ago. “It is remarkable that such a level of thumb dexterity, similar to that of people living today, would be observed in hominins alive two million years ago,” says Katerina Harvati, a paleoanthropologist at the Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Paleoenvironment, University of Tübingen (Germany). Now a new study combines the ancient evidence of fossil fingers and thumbs with cutting-edge computer muscle modeling to conclude that South African hominins boasted flexible, capable thumbs much like ours as far back as two million years ago. Because developing dexterous, opposable thumbs pushed our ancestors to make and use tools, eat more meat and grow bigger brains, scientists have long wondered if such thumbs began only with our own genus, Homo, or among some earlier species. Strong and nimble thumbs meant that they could better create and wield tools, stones and bones for killing large animals for food. But for our ancestors, the uses were much simpler. So much of modern-day life revolves around using opposable thumbs, from holding a hammer to build a home to ordering food delivery on our smartphones.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)